Conquering the Fann Mountains

“Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out going to the mountains is going home; that wilderness is a necessity…” – John Muir

Most people who actually know where to pinpoint Tajikistan on a map have heard of the mountainous wonders of the Pamir Highway, a recurring destination listed on many adventurers’ bucket lists; but the rest of this rugged country remains more of a mystery. Tajikistan is home to some of the best adrenaline-pumping spots, ready to provoke any explorer into action. One of the best places to trek is the Fann Mountain range, located in the north-western part of the country. A region rich with turquoise tinged lakes and enough high-mountain-pass-obstacles to keep any altitude junkie happy, it reminded us yet again why we love escaping to the wilderness by foot.

This was our first “luxury” trek, in that it was the first time we did not have to carry our big packs and tents on our backs for a week, but were instead accompanied by chaar har (four donkeys) which we named Padrud, Penji, Zahra and Shing after the places we passed on the way. To make it even more “luxurious”, my wonderful sister Camilla joined us all the way from Rome for the adventure, ready to conquer the peaks with us.

We set off from Dushanbe in the early morning towards Penjikent along the Zerafshon river where the Community-Based Tourism office (CBT) through which we organised the trek is headquartered. The road from Dushanbe to Penjikent is an experience in itself. Jaw-dropping cliff edges, 4000m high mountain passes and countless Chinese trucks. To make it in one piece, you have to go through what we have named the “Tunnel of Terror”. Not one for the claustrophobic, the old passage was supposedly built by an Iranian company; roughly carved through vertiginous rock. Pitch-black, flooded and dotted with pot-holes, we hold our breath in what seems like an interminable journey, past the outlines of dimly-lit workers employed by the Chinese company that is now trying to salvage the leaky shaft. It is another reminder of the horrific working conditions that certain professions around the world still endure.

From Penjikent we make our way to Padrud, our first home stay before we start our six-day trek nice and early the next day. Todchi and his family – our hosts for the night cook us the best dumluma we have had so far, it is impressive how a simple dish of cabbage, carrots, potatoes and lamb can taste so differently from different hands. We meet and share our meal with our trekking guide, Hakim who hails from “the capital of America in the Fanns – Shing, as in Wa-SHING-ton”. Over çay, they tell us stories of the Soviet era, of land ownership, family policies and how mothers with more than five children are referred to as “Hero Mothers”; reminding me of the “Médaille d’Honneur de la Famille Française” which honours families with more than eight children with a golden medal.

The stunning location of the home stay perched on a gushing glacial river also meant a rather sleepless night for Nico who could only think of pee-ing, inspired by the unrelenting torrential noise 50cm away.

Day #1 Padrud – Kiogli – Tovasang Pass

In the morning, our donkeys and their caretakers Davlak and Ignogbeek (I kept thinking of eggnog and bird beaks the first hour to make sure I got his name right) arrived and we began loading our supplies. I felt a pang of guilt as they strapped the heavy bags onto the donkeys’ backs, but they laugh with a knowing look as in “foreigners always get more attached to the donkeys”. And off we go, our trekking crew complete with Nico, myself, my sister Camilla, Hakim, Ignogbeek, Davlak, Penji, Padrud, Zahra and Shing.

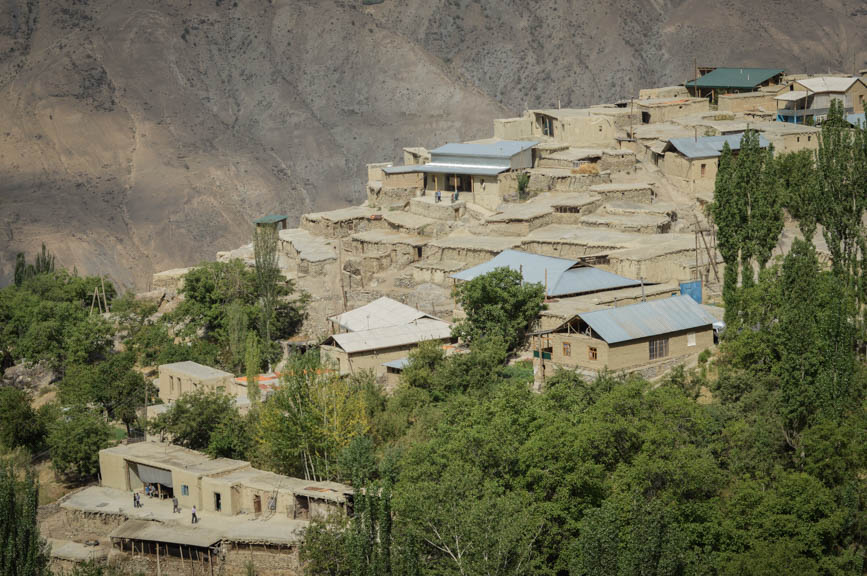

The ascending climb starts in the Seven Lakes region where one mineral sapphire lake cascades into another one below, a string of water bodies connected to each other through bubbling holes in the edge of the rock. We pass the teal-tinged Hurdak Lake at 1900m before following the contours of the Marguzor Lake at 2139m. From there we scale to the village of Kiogli, set just below the peaks with a sweeping view of the valleys below. The children wave enthusiastically as the women shy away in their colourful veils and several groups ride pass us on their donkeys, by far the most conservative area we have been so far to in the country. It is laundry day in Kiogli and as the women lay out their massive carpets to dry on the hill, we head to the local blacksmith to get a new pair of shoes for Shing the Donkey. Ouch.

As the afternoon approaches, we are thrown back by the heat, surprised by the rising temperatures at 3000m and my stance begins to resemble a crawl more than anything towards the peak. Suddenly the wind picks up and we are almost there, we can see the Tovasang pass, just a little closer. It seems so close and yet as if on a treadmill, the mountain never seems to move towards you…a relentless day of steep slopes, but miraculously we make it.

We arrive at one of the best campsites on the trip, the grass is soft and green and the snow dotted peak of Gardish (4715m) stares right back at us, all to ourselves. The first day is always the hardest, but it was definitely worth it.

Day #2 Tovasang Pass – where the Sarimat and Archamaidon Rivers meet

The chilly air wakes us from our light sleep, but as I stretch out of our cramped tent, the sun is still that golden shade of morning reminding you why you slept on that literally rock-hard floor. This is what we walk for, to be at the top of the world and alone. Well, alone with a boiling kettle, some donkeys and a small bunch of people, but you get my point.

After a breakfast of day-old-naan and a boiled egg, we pack up camp, load the donkeys and are on our way. Today is the complete opposite of yesterday, the gradient is down down down as we descend into the Daravsinoy Valley and follow the Sarimat river. The snowy peaks chaperon us all the way down, puffing up as we get farther way, looking larger than life the further we walked. Yesterday I dreamed of a downhill slope, though this plunging incline now left my toes and knees begging for relief. I quickly decided my favourite type of slope was actually flat.

One of the best things about hiking and trekking is that you learn to appreciate everything more, be it that sip of water or the incredible cooling effect of glacial rivers on your tired soles. The powerful Sarimat river is transparent ice, with specks of ultra-marine in its undertow. The feeling of just dipping your toes in it after hours of hiking brings inexplicable joy. In the heat it is irresistible and our laughter finally convinces our guide Hakim to take a dip too. He is enduring through the last few days of Ramadan, compared to all my internal whining, I am in awe of his ability to avoid passing out, not a sip of water passed his lips.

The valley is home to several small villages, making you wonder how they survive without depending too much on the outside world. Being so inaccessible, we ask how they got there in the first place.

Most of them have managed to create abundant apricot and potato farms in the harsh landscape, providing some level of self-subsistence.

A fairly easy day, we set up camp where the roaring Sarimat trickles down into a timid stream and the Archamaidon river comes to merge. Hakim tells me it is my turn to cook, so it is camping kitchen improvisation 101, so long to our “luxury” trek.

Day #3 The two rivers – Zimtud

We leave the two rivers where they join, the turquoise Sarimat blends with the chalky Archamaidon, disappearing into each other until they look like the left over water from multi-coloured dipped paintbrushes.

Today is the day I prayed for, mostly flat, but flat also means the least interesting landscape so far – you obviously have to work for the best views! We follow the river for most of the day, the wind sprinkling dust and sand to coat our blistering hot skin. For the most water-abundant country in Central Asia, Tajikistan is surprisingly dry, anything within 10 metres of the river has the capacity to sprout green, anything beyond that is dry bone.

We pass a small village called Gazza (yes, with two ‘z’s) and there we find our highlight – a zardolu farm. The apricot farm has trees laden with orange gold, a gentle shake of the trunk rewards you with a shower of soft fruit. Zardolu literally means yellow plum and here we taste for the first time a kind of apricot-plum hybrid that is pure honey. I would never have put apricots in my top five fruit list, but this variety may have to change my mind. The Central Asian region is well-known for its apricots, but since it is difficult to export fresh, most people have never tasted this smooth skinned, vanilla infused juice bomb. This farm itself had at least five varieties of the yellow plum, ranging from pink, deep red, saffron and golden amber. A boy taking care of the farm kindly offers us buckets of fruit and stuffed with apricot nectar, we snooze under the leafy canopy for awhile, before tearing ourselves away to continue the journey to Zimtud.

Day #4 Zimtud – Guitan – Chukurak Lake

In Zimtud we are spoilt by our homestay family, lavished with sweets and given threatening looks by the grandmother if we did not finish our second portion of plov (the national rice dish of what seems like every Central Asian country). After a restful night (on double mattresses!) we gorge on sour cherry jam and more fried eggs before leaving for our mountain pass of the day. It is Eid Iftir, finally the day of celebration after a gruelling month of Ramadan in the summer swelter. Everyone is out on the streets and happiness is in the air. We get invited left and right for plov at nine in the morning.

In the village of Guitan, even the donkeys are celebrating with their sand bath, rolling around and grunting in the dust. Green almonds are ripening on the trees next to more apricot orchards as we endure the ascent towards Igrok Pass at 2500m.

Beyond the top of the pass we encounter our first Tajik nomad village. Their tents are round compared to Uzbek ones, resembling an elongated cylindrical yurt. We are welcomed by dog barks and children as we enter the village and then to our surprise, guided into a tent where a feast awaits us. Davlak and Ignogbeek are already there, wolfing down bowls of yoghurt.

This is where I have a confession to make, nomad-made yoghurt and me do not always get along. At the mention of yoghurt, a feeling of dread descends upon my taste buds, shrinking in fear at the suggestion of strong smelling acid yoghurt memories. Turns out I need not have worried, because this was the best yoghurt I have ever had. I swear. Smooth, creamy, slightly sweet and topped with a huge dollop of thick beige cream. As Hakim cleaned his yoghurt bowl with his fingers (giving new meaning to finger-lickin’ good) plates of plov appear. Rice simmered in oil with carrots, onions and chunks of lamb, this dish is not for the faint-of-heart, but much loved in Central Asia, apparently by almost everyone except Hakim who later revealed that he could not stand plov; what misery that would be when it is the most commonly offered dish!

The nomads once again surpassed themselves in hospitality, treating us to so much for nothing in return. Eid Mubarak!

As we leave, they invite us into another tent and we are greeted by about twenty women and children, friendly faces look up at us and though we do not speak the same language, we feel great sincerity and warmth. Everyone is honouring Eid Iftir with a big feast as the women and children dig into their own platters of dried fruits, nuts and of course copious amounts of plov.

We leave the nomad camp full and happy and make our way down to our camp for the night. Nestled between imposing rocks, Chukurak is the definition of tranquility. The water is still, the air is crisp as we dive in for a freshwater “bath”. We go to sleep that night wishing we could stay longer, keeping this place to ourselves, under the clear sky and the stars.

Day #5 Chukurak Lake – Kulikalom – Bibijon

After a breakfast of five-day old naan and another boiled egg, it is raining, it is pouring on day five as we make our way up and over the Govkhona mountains. Through the mist and the raindrops we are rewarded with a network of lagunas, the colour of a Maldivian atoll weaving through islands topped with rugged tortured trees. The Kulikalom Lakes. Named after the Russian explorer who first climbed them, the Maria Mountains tower over the lakes that provide some light under the gloomy clouds; thick parts of glacier hang onto the edge of the steep slopes, threatening to crash down at any time.

The land depression in between the lakes is almost surreal, trees twisted as if by sorcery and burnt before being reborn into the cracked dry earth surrounded by all this water. Beyond lies Bibijon Lake – ‘Grandma’s Lake” where we will camp for the night.

From the tent I hear Nico having a conversation with a bunch of people who had been attempting to fish from Bibijon just moments before, the constant repetition of the word “Nooo-oooh!” by a voice I did not know raised my curiosity. The group of friends, all born in 1988 went to school together and were on their yearly trip for a few days in the mountains. They invite us to their well-equipped three man camp for çay and biscuits and in our mutually limited language skills we exchange some personal histories. One of them used to be a taxi driver in Russia, now he is working back home. He is a representative example of the large diaspora of Central Asians in Russia. In 2013, 48% of Tajikistan’s GDP came from remittances of migrant workers in Russia. Almost half of working-age males in the country have worked in Russia at some point in their lives; mainly in the construction sector and many Russian families hire Central Asian nannies for their children.

When meeting new cultures, humour knows no language barriers and after we have a few laughs at Nico trying on the classic blue velvet Tajik wedding coat, we leave before dark as they wave at us from their side of the river.

Day #6 Bibijon – Alauddin Pass – Alauddin Lake

Today is the day we climb Alauddin Pass and consume six-day old naan. All the hiking we have done the previous days help us climb this vertical slope with relative ease. Huffing and puffing our way up to 3850m, this is the first time we see other hikers through the drizzle. For 5 days we have been alone, suddenly we find ourselves in the popular Alauddin part of the trek where most itineraries bring their groups. The victory of reaching the top is no less sweet. We are encompassed by peaks of 5000m and it truly feels like we are at the top of the world. Waiting for the clouds to clear, we stare in silence as the ice capped peaks reveal themselves to us.

The rain does not have our patience though as it decides to bucket down at that moment, forcing us to make our way rapidly down the pebble strewn slope towards Alauddin Lake. The lake is another turquoise wonder, this time a darker shade of cerulean borders its edges. Somehow we are less perceptive to beauty when we are soaking wet and cold, and we set about preparing our camp site for the last night oblivious to our surroundings.

The morning is another story, the lake a calm mirror in the sun as we celebrate its own reflections, the type you cannot turn away from. Looking up at our surrounding peaks, we could not believe how much we had walked to get here, through the deep valleys and the high passes, purple toes and all. Another trek has come to an end, but no matter how much you suffer each time, you know you want to do it again. The joy of collapsing onto your rigidly thin tent mattress every night, the adrenaline and exhilaration of reaching the top never gets old and that pure giddiness that explodes into your cheeks every time you bite into that juicy zardolu fresh off its branch.

2 Comments

Marc

August 31, 2014This is epic! Like travelling with you guys. The pictures stunning as usual…

Conquering the Fann Mountains | Caravanistan

March 2, 2015[…] This post was written by the Funnelogy Channel and first appeared here. […]