Nomadic Life with the Bakhtiari

Squinting through my sleepy eyelids, a huge snow-capped mountain range appears out of the corner, glimmering white between the shadow of my dark eyelashes. We have arrived in the Khourang. The previous day in Tehran, our wonderful hosts at Cenesta (Iranian Centre for Sustainable Development) had asked us whether we would like to join another couple heading towards the Zagros Mountains for a stay with the Bakhtiari nomad tribe, we had no specific plans and jumped at the chance to follow the unexpected. The dynamic duo of Catherine and Taguy who founded Cenesta have worked day and night since the 80s, and still do, to build up Iran’s largest environmental NGO. Cenesta does excellent work in partnership with some of the pastoralist tribes in the country, documenting nomadic life and examples of traditional conservation methods for maintaining ecosystems and slowing desertification in the regions they inhabit.

The Bakhtiari of Iran traditionally held pockets of power in Persian history, mainly dominating the oil-rich region of Khuzestan. Governments have tried to settle many nomadic tribes around the world in order to better control them and the land they live from and Iran is no exception. Despite hardships and obstacles, Iran still has about 1 million 300 000 nomads and the Bakhtiari are one of the 700 nomadic pastoralist groups in the country. Their name derives from the Persian “bakht” meaning “chance” and “yar” meaning “companion”, to be best translated as “bearer of good luck”.

We set off at one in the morning from Tehran, the city finally quiet and dark as the four of us squeeze into the yellow taxi which we would all affectionately come to call “The Machine” and tried to get some sleep for the twelve hour drive to the Khourang. The Khourang Valley sits at the foot of the impressive Zagros mountain range and protects the source of the Zayandehrud, a river powerful and violent at its source but which dries up to a thin trickle along the way, starved by all the diversions it has suffered and disappearing altogether in the cities it previously gave life to such as Esfahan and Yadz.

Daniel our road warrior of this Bakthtiari episode is sweet, fun and with a tone of voice just a notch too high. This humorous Tehrani made sure we got to point A, B and C safely, all the while indulging our curiosity with snippets of local slang and introducing us to his favourite game – Poo. His phone’s screen is neon green as a miniature cartoon shows up, brown and gloopy as Daniel squeals “Pooooo!” We all look incredulously and start laughing as he demonstrates the need to feed the animation regularly, a poo-version of the Pokemon.

He brings us to the village of Sheyk Alikhan where we meet Omid, Cenesta’s Bakhtiari contact and member of the family we will be staying with. The crisp morning air is a nice change from dusty Tehran and we are immediately brought to the first of our many tent visits for breakfast where we meet the sisters Farzahne, Abzahne and Farouzahne. Their little brother Mozen plays hide-and-seek behind his sisters’ colourful dresses as we attempt to learn a few more Farsi words. A feast is spread out on the floor inside the tent, plates of omelette, bowls of sticky treacle dates, dourgh sabzi (thick savoury yoghurt with herbs), rohan (sheep butter), mountains of lavash bread and pots of çay to wash it all down.

We begin our series of courtesy visits and back in the village we head to Mohammed Reza’s shop where the men had as much, if not more fun than Nico dressing him up in traditional Bakhtiari garb – a long piano-striped choura topped with a black khola.

Mohammed Reza shows me bags of kheshk – dried dollops of sour yoghurt resembling balls of chalk, much loved in Iran and the fragrant leemu, dried limes, essential for the Iranian kitchen.

We take “The Machine” deeper into the valley, through never-ending verdant pastures and different shades of sandy grains, ash blonde and champagne. First stop, another relative’s tent where we are offered the qalyan (water pipe) and home-made dourgh, fresh from the animal skin pouch itself. No matter how much I try, the tangy tartness of the yoghurt drink is too much for me to stomach, but luckily there is black çay with copious amounts of sugar instead. The sugar here is stored as huge crystal cylinders, snipped at from time to time with tough pliers and served in generous chunks.

Waving goodbye to chimes of “khodafez” (bye) we make our way on foot, base camp still an hour away. The path ascends through an ever leafier valley, pass walnut orchards and garlic fields till we see someone eagerly waving at us among a flock of hennaed sheep, the remarkable Mohnessa.

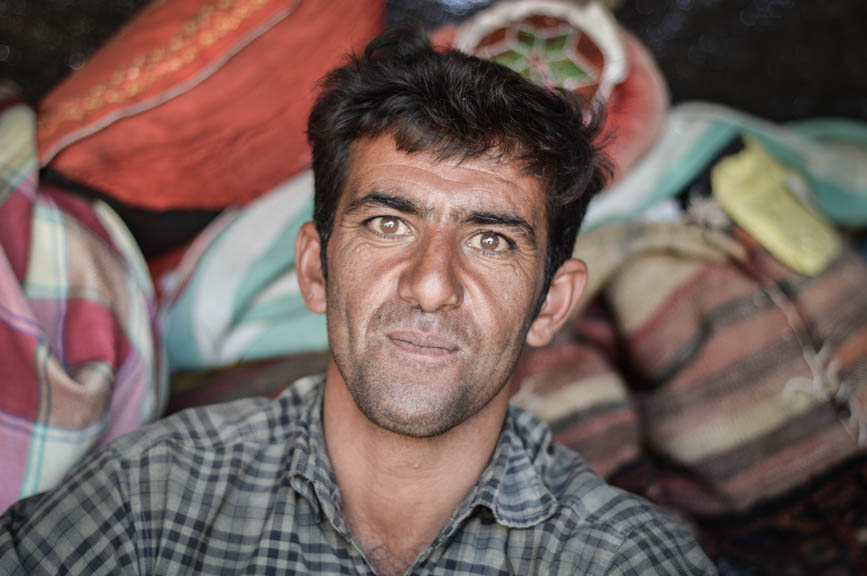

Omid’s mother, shepherdess and head of the Ardshiri family is instantly warm, kind and gracious. She engulfs me in a big embrace, putting me at ease and immediately making us feel welcome. Of her thirteen children, we meet seven of them at their summer quarters (sardsÏr).

For three months they stay here with their sheep, goats, horses and chickens, before taking one month to move back to their winter quarters in Khuzestan where they live in a house and the children go to school. Usually about ten families migrate together and while they each have their own space, most of their extended family’s tents are at walking distance or a quick drive away.

Once we settle in, everyone gets busy preparing dinner. Meat is eaten on average every two days and wild herbs are collected nearby. Often garlic is sliced and soaked in bags in the river till they lose their sting, ready to be eaten raw as a refreshing snack. They grow their own beans, but buy rice at the market, increasingly expensive over the years. Tonight we have berenj bo tara ba dourgh (rice with wild herbs and yoghurt). Yeay. More yoghurt. As the rice brews outside over the fire, watched over by the sisters Sonya and Zahra, Mohnessa gets busy making the lavash.

Flour, salt and water are massaged into a massive ball of dough, flung around at the speed of light as Mohnessa rolls, flips and spins, paper thin discs of dough onto the scorching metal dome. Suddenly a pile of hot lavash is by her side, greedy hands impatiently ripping into the burning layers, too good to wait.

That night, a stunning moon illuminates our camp as we sit by the fire, somehow exchanging jokes in our limited communication, shared humour being our common language. Topics range from Amir’s horses to Omid’s translation skills. Since we arrived, Omid has been taking notes of english words with the same obsession with which I have been noting down farsi words. His family laughs as he pulls out his one sheet of paper, grey from multiple scribbles and exclaims, “Here You Are!” I find this very amusing until finally realising that it is a direct translation of “Befarma”, which is close to “Welcome” or “Please, after you.”

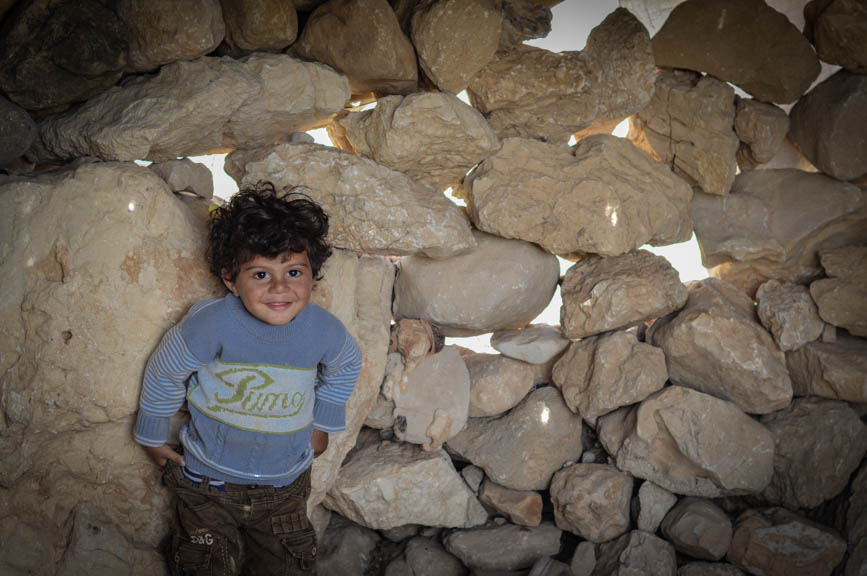

The sheep and cows return to their stone-stacked “courtyard” in front of the tent and we fall asleep among the flower-patterned mattresses, with the animals’ bells and grunts lulling us into a deep sleep. In the morning, the warmth of the sun gently greets us and inquisitive faces are staring at our motionless bodies, waiting for signs of life. It was funny to see that we were just as much a curiosity to the family as they were to us.

We tell Omid we want to climb up the mountain behind their camp, to have a better view over the valley. He gives us a look betraying his thoughts that maybe we are crazy, why on earth do we want to climb up the hill? His cousin Amir agrees to take the mad farangi (foreigners) through the bushes, first to see his beautiful horses then on up to the peak. Everyone feigns surprise and laughs when Omid abandons us halfway saying he will go for çay at the neighbour’s tent and wait for us there.

Halfway up the hill we realise it was a failed mission from the start, the innocent looking bushes are actually thorny traps, constantly prickling as we creep up with determination. After an hour, we are forced to admit that maybe the farangi are bonkers after all and let’s just go for çay.

We meet another family who shower us with food and drinks, their children sit with us and we try to speak in gestures. When their little girl with the wild haircut shows up, Nico comments that it is fashionable and suddenly everyone is calling her “Fashion” and laughing. Discussing food, the two young boys catch on immediately to their favourite word, “spaghetti macaroni”, some words travel faster than others!

The hospitality of the Bakhtiari nomads we met was overwhelming and though our stay was short and language skills lacking we felt as though we had great conversations. Even if they were mainly limited to “spaghetti, macaroni!”. It is easy to romanticise nomadic life, not the modern trend of equating long term backpackers/travellers with nomads, but the centuries old tradition of moving with their flock, making a living from the land. They appear independent, mostly self-sufficient, live in a beautiful environment and are mostly sustainable. It is also easy to assume that nomads or indigenous people live the way they live because they have experienced nothing else, but Mohnessa has travelled to places as far as Mali and Singapore (to attend world nomads conferences) and still lives the life she grew up with. Whether it is a choice I do not know, we’ll have to go back for a longer chat next time…

That afternoon, Omid’s new favourite word becomes “Let’s mooove” – “berim/herikket” and soon we are off, back to our tent and to Daniel’s great relief, back to “The Machine”.

1 Comment

tammy

July 23, 2014So interesting! Loving reading hour blog! The little girl’s hair style,I thought it was a wig??!!