In the Footsteps of Tibetan Pilgrims at Labrang

It smells like Tibet. Of yak butter melting in candle flames and dark-pine branches smoking through layers of heated stones. The scent jolts me back to my time in Lhasa, a combination of ingredients that is uniquely Tibetan. Prayer beads, small and large, sombre and bright, adorn the wrists and necks of passersby. Colourful sashes, hot pink, burgundy and violet hold up their bulky draped cloaks, extra long sleeves protect against the cold and double duty as wrap-arounds or scarves. Cheeks are red from the wind, foreheads brown and weathered from the sun. It is cold and it feels like Tibet.

Only this time we are in the Gansu province of China, part of which is formed by the traditional Tibetan region of Amdo. The journey from Lanzhou to Xiahe goes up. Up pass the terraced potato fields of a narrow valley, leaving the concrete blocks of the Gansu capital behind for village houses roofed in black tiles. The river that runs through it is watched over by golden-domed mosques, one for each hamlet. As we get closer to Xiahe, the mosques are replaced by golden-tipped stupas, Tibetan chortens, representing major events in Buddha’s life.

Xiahe is long and slender, most life radiates vertically along the town’s one main road. Brand new cotton-candy-coloured apartment blocks, empty of tenants, welcome you at the mouth of the city before morphing into lamb skewer stands, muslim naan ovens and halal 清真 restaurants signs. Pushing on deeper into the valley, you arrive in “Tibet”. At the end of the main road lies the gate to the Labrang Monastery (བླ་བྲང་བཀྲ་ཤིས་འཁྱིལ་), one of Tibetan Buddhism’s most important monasteries outside its Autonomous Region.

The Labrang Monastery was one of the largest Buddhist monastic universities and one of the six great monasteries of the Geluk School of Tibetan Buddhism, the “Yellow Hat” sect often closely associated with the current Dalai Lama. During the Cultural Revolution, monks were sent to work in the fields, deserting Labrang, but they returned to reopen it in 1980. Its walls now house around 2000 monks. Founded in 1709, the monastery played a large role in the conflict to maintain regional autonomy between 1700 and 1950 and has always been in the middle of a strategic melting pot of Han Chinese, Hui Muslim, Tibetan and Mongolian cultures. Today, thousands of pilgrims come to make their prayers at the cultural heart of the Tibetan Amdo region.

The bridge over the Sangchu river leads to the first prayer wheels of the kora སྐོར་ར. Persimmon red, gold calligraphy and blue green waves spin dizzily as the pilgrims push the hexagonal wheels into motion, a blur of symbols as mantras are repeated under their breaths and malas (prayer beads) rubbed and counted.

Women in braids and men in hats walk round and round, the heels of their shoes scuffed and dusty, but nothing deters them as they follow the route, round the monastery walls or looping a white chorten, a mission to fulfil. The kora is a Tibetan word meaning “circumambulation” or “revolution”. Usually it is part of a pilgrimage, ritual or ceremony where the believer walks round a sacred object or place. At times this includes large sites, such as sacred mountains and high passes. Following the path of the sun, the pilgrims proceed clockwise, chanting and spinning, waiting for empowerment from this holy site. We walk in their footsteps, mesmerised by the whirling, hypnotic swirls, but I am temporarily distracted by the pairs of shoes shuffling before me, all seemingly one size too large for the feet they protect.

On a sunny morning, around 11am, people within the walls of the monastery start migrating towards the courtyard of the Grand Sutra Hall. Tibetan pilgrims and camera-toting tourists alike swarm towards the steps leading up to the entrance, awaiting something they have been told will be worth it. One by one monks in crimson robes appear, taking up different positions on the steps, some on the lower right, some on the upper left. One by one they begin a chant, like a choir, one group holds the melody, another the beat and another the stable monotonous background hum. One by one they put on their saffron crescent hats, like a sea of yellow-crowned bishop birds looking up. They sing in unison, their harmony only broken by the occasional tardy monk rushing to join his ensemble.

At times it can be easy to focus on the camera clicks, reminding you that you are not alone, but there is a moment when you decide to follow the throaty tones, basal hums and soft rhythms and I felt a lump rise in my throat. For an instant I forgot where I was.

Two Tibetan horns, also known as a dharma trumpets moan from the roof, and pilgrims begin rising to their feet. Palms are joined in front of mouths and knees are bent to kneel, shins touching the cold stone slabs as they lower their foreheads to the ground and repeat. The monks remove their shoes and there is silence. The crimson tide turns in one swift motion and enters the monastery.

The steps are now empty, save for hundreds of boots, an ocean of black velvet rimmed in christmas-red and green.

Inside, the wide hall is held up by antique wooden beams, the walls adorned with images of Buddha painted as thangkas, rows of pillows line the floors as the monks chant on in semi-darkness. The beat speeds up as drums and cymbals join in the chorus, solid and baritone. In the middle section sit six monks sorting through offerings, three of them rapidly separating piles of cash from prayer papers, three of them counting stacks of single note chinese renmenbi. The spell is broken.

The pilgrims enter next to join the ritual, some of them wearing a single glove to protect their right palm from a day of rotating wheels, others with stone slabs attached to both hands as they perform full prostrations along the kora.

There is a wider kora on the hills behind the monastery, the sacred outer circle. We pass a small village behind the monastic walls, shrunken alleys fringed by boxy Tibetan houses, patios covered in glass to let the light in. Here, the smaller Red Sect is performing their chanting ritual, a louder and wilder version, horns and drums coming together in ceremonial cacophony. These monks are wrapped in red and white organza, their longish hair surprising in contrast.

The climb is slow, from 2850m, we ascend about 400m more. The mountains surrounding Labrang are green and luscious, looking more like a Hawaiian island than the rolling grasslands of Gansu. At the top, a pillar of prayer flags is dancing in the wind, the multicolour cloths fraying and disintegrating, their messages sent into the heavens.

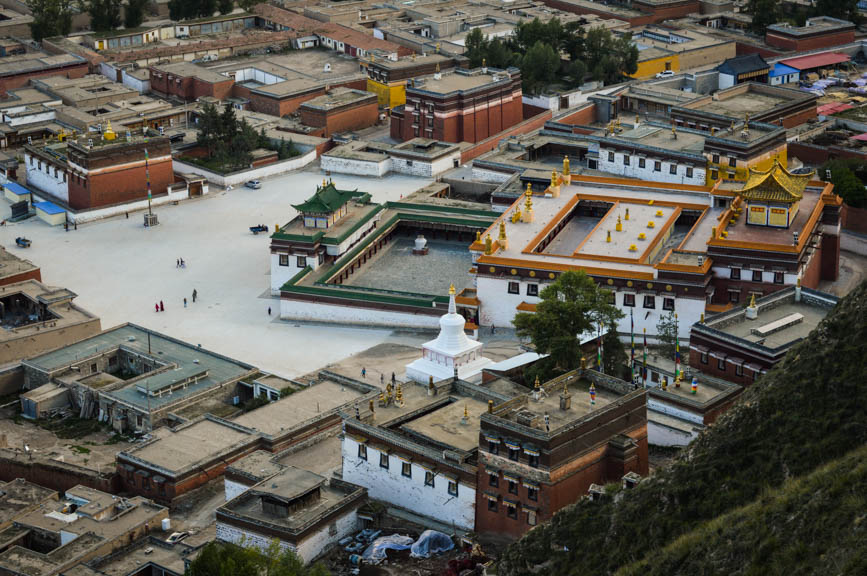

From here, the town is laid out below us, we gasp as we realise we have only seen a quarter of what lies within the monastery’s walls. Across from the principal buildings are neat rows and blocks of accommodation, houses surrounding mini internal courtyards, repeating their pattern again and again. Grey and symmetrical.

We wait for sunset to descend, and we find the pilgrims where we left them; circling the white chorten, time and time again, their mantras and prayers released clockwise into the sky.

1 Comment

Romain

October 5, 2014Toujours un texte aux petits oignons et de fabuleuses photographies. Félicitations !